Your web browser (Internet Explorer) is out of date. Some things will not look right and things might not work properly. Please download an up-to-date and free browser from here.

4:32pm, 16th December

Home > News > The yin and yang of El Niño – Auss...

The yin and yang of El Niño – Aussie dry as Peru drowns

18/11/2015 9:00pm

> From the WeatherWatch archives

The world’s largest ocean is hosting the yin and yang of El Nino.

On one side of the Pacific, large tracts of Australia are gripped by drought triggered by the phenomenon. On the opposite side, the desert coastline of Peru is preparing for devastating rain.

Scientists warn Peru faces one of the strongest El Ninos on record.

In the next few months it could deliver a multi-billion-dollar damages bill from landslides, floods, failed crops and the collapse of the world’s largest anchovy fishery.

“Peru, along with Australia, is one of the worst affected countries in the world from El Nino,” said Angel Cornejo, professor of climate studies at the National University Agraria in the Peruvian capital, Lima.

“Poverty is the problem here. People live in places that will flood. They are very poor and they have nowhere else to go.”

The government declared emergencies in 14 districts, including Lima, and funded preparation efforts.

The last severe El Nino, in 1998, had a calamitous impact causing floods in the Andes and on the coast, destroying more than 12,000 homes, damaging half the country’s transport infrastructure and leaving a $A4.9 billion repair bill.

In Peru’s second largest city of Trujillo, residents are bracing for torrential rain which may begin later this month.

The desert city and its population of 1 million people usually receive less than 50 millimetres of rain a year.

During the last major El Nino, 3,000 mm of rain fell between November and March.

“My house was like a lagoon. Water covered half of my body,” Doralisa Cruz, 70, said.

“There was a fast-flowing river [which appeared nearby] and lasted two months. Only two houses resisted the flood. The others disappeared.”

Ms Cruz lives in El Porvenir, a suburb of Trujillo, where more than half the population is below the poverty line.

During 1998, rivers carved their way through Trujillo and its cemetery, carrying bodies into the colonial town square.

Since then, internal migrants from Peru’s mountain region have moved to the city and some have built homes in the dry river beds.

“If El Nino hits, our major fear is that three dry river channels will start to flow,” Olga Castro, head of risk and disaster Management at the city’s Civil Defence Service, said.

“We went to the places where the channels were and we found that people have bought pieces of land and they have built houses. We told them to leave but they do not want to.”

Ms Castro warned if there were floods, diseases such as dengue fever and cholera would be major problems.

She said the Civil Defence Service was encouraging people to prepare their homes and clean their roofs to prevent them collapsing, but few people have money for protection works.

Peruvian fishermen bear the brunt of climatic event

During El Nino, the warm water from Indonesia moves east and the prevailing winds reverse, travelling from west to east, generating heavy rainfall in parts of South America, and in particular Peru’s northern coast.

Peruvian fisherman were the first to name the climatic event, calling it El Nino de Navidad or Christmas Child.

In Trujillo’s beachside suburbs, it is the fishermen who are experiencing the initial impact of the latest El Nino as the ocean becomes warmer.

“We normally have 80 kilos of fish a day, now it’s just enough for personal food,” Victor Arzola, vice-president of the Traditional Fishermen’s Association in Huanchaco, said.

Here, fishermen use traditional cacallito de totora boats made from reeds.

“During the last big El Nino we stopped fishing and worked as builders,” Mr Arzola said.

Peru has the world’s largest stock of anchovy, but fisheries professor Luis Icochea from the National University Agraria said this year’s catch had more than halved to 2.5 million tonnes and was expected to decline further over the next six months.

“The anchovies have travelled south and dived deeper where the fishermen’s nets cannot reach, because they don’t like the warm water,” Professor Icochea said.

“Next year will not be good because the anchovies will have problems reproducing.”

– Weatherzone.com.au/ABC

Comments

Before you add a new comment, take note this story was published on 18 Nov 2015.

Latest Video

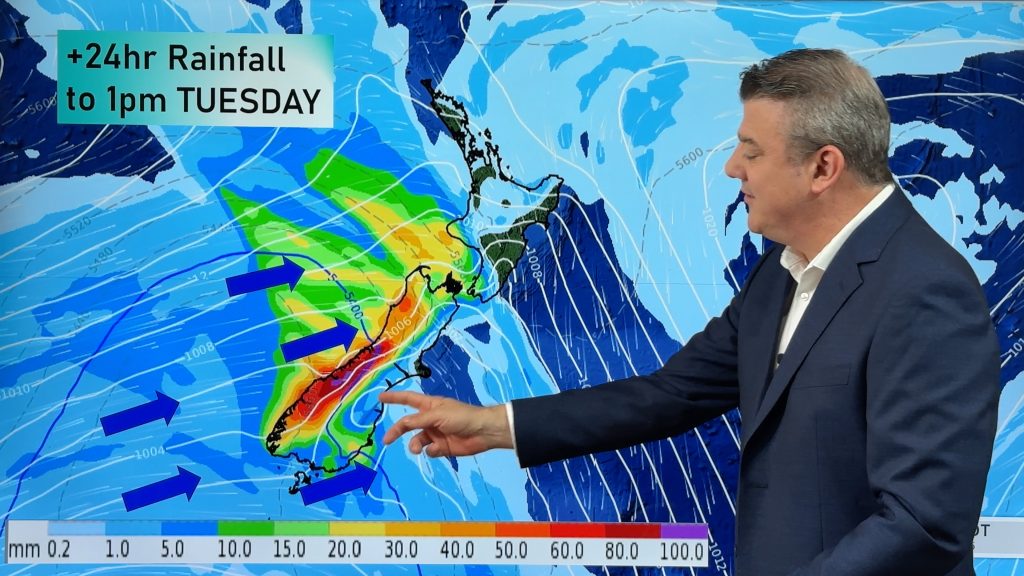

Spring-like until Christmas (NZ’s 11 Day forecast!)

Severe gales, heavy West Coast rain, and temperature fluctuations are on the way as spring weather returns following a much…

Related Articles

Spring-like until Christmas (NZ’s 11 Day forecast!)

Severe gales, heavy West Coast rain, and temperature fluctuations are on the way as spring weather returns following a much…

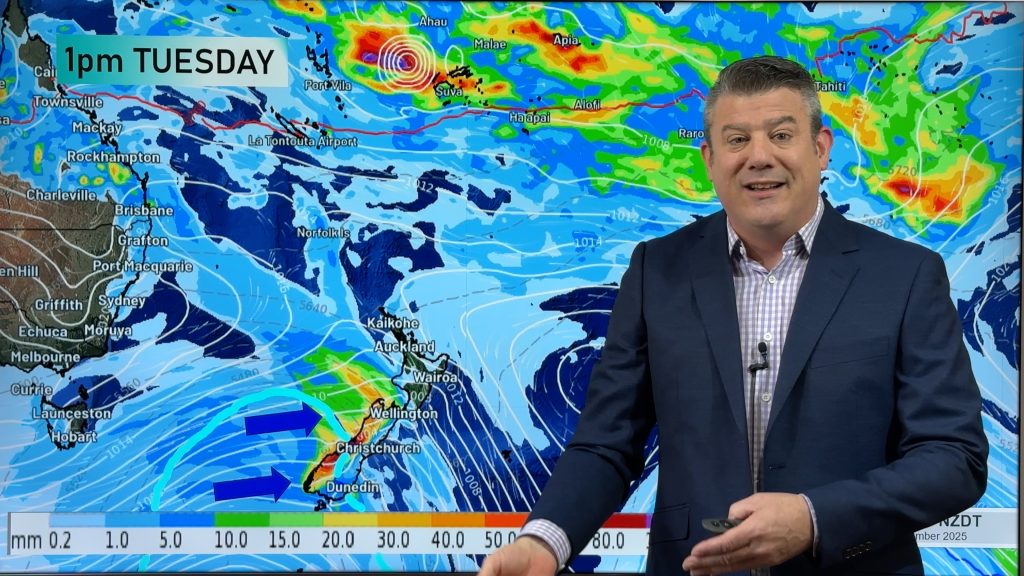

NZ: Spring gales, temp drops (& spikes) + Fiji has a tropical low to monitor

We have our first forecast for Christmas Eve & Day today, but this coming week looks spring-like as a colder…

Windy westerlies return next week + Vanuatu/Fiji tropical cyclone risk update

(No video Friday, next update is on Sunday) — NZ has a cooler/colder change coming in on Friday as a…

Navigation

© 2025 WeatherWatch Services Ltd

Add new comment