> From the WeatherWatch archives

In the days after Christmas, the 100-year-old Salisbury Swing Bridge in Golden Bay was torn from its wire moorings and washed away in the region’s worst flooding in modern history. Campsites in Tasman were evacuated and homes cut off. The Aorere River, which can usually be forded by hikers, turned into a mucky torrent, flowing at 3500 cubic metres a second.

The fast-moving downpour gave New Zealand a glimpse into a climate phenomenon which has left its mark on several continents. Devastating floods this year in Australia, the Philippines and Sri Lanka and last year in South China and Pakistan are all the handiwork of “the girl” – La Nina, the female relative of El Nino.

During El Nino, warm water sloshes west to east across the Pacific. During La Nina, it occurs in the opposite direction.

The weather cycles take Spanish names because the first people to notice the shifting temperatures of the Pacific were Peruvian fisherman. When their anchovy stocks plummeted in the 1700s, it was blamed on a strange, warm current in the Eastern Pacific.

Those warm waters produce greater deluges in South America and a drop in the fish catch.

The event was named El Nino, “the Christ child”, because it arrived at Christmas.

These two disturbances in the tropical Pacific are now known to have far wider effects than hurting the fishing trade. They are second only to the four seasons in influencing global weather.

La Nina was the catalyst for Australia’s monsoon rains this week, which quenched its drought-stricken eastern region and flooded some of its cities.

It is not known what prompts the pendulum swing between El Nino and La Nina, but it is believed to be caused by complex interactions of ocean and atmosphere movements.

La Nina has the opposite effect to El Nino, by cooling the Eastern Pacific.

That cooler water forms a “cold tongue” across the equator, and shoves warmer waters around Australia.

The warm currents reach New Zealand too, bringing warmer weather and more rain, but with less impact than in Australia.

Yet though the North Island gets above-average rainfall and more storms, the South Island dries out.

We are more familiar with El Nino, because the second half of the 20th century was dominated by El Nino patterns. But La Nina cycles, which come at intervals of several years to a decade, have left an imprint in Australia and New Zealand too.

Two major La Nina cycles stand out in Australasian history.

In 1973-74 (similarly to 2011) the Brisbane River broke its banks. Wild weather in Queensland flooded 6700 homes and nearly sank a 70,000-tonne oil tanker.

In 1988-89, grass fires tore through a tinder-dry Central Otago during a La Nina event. It was also the warmest year in New Zealand’s history, and caused a severe drought in the South Island.

In the words of the MetService weather ambassador, Bob McDavitt, “No two La Nina events really follow each other exactly”. While La Nina is known to pelt the North Island with rain, the last event in 2006-2007 pushed the Waikato into drought, which eventually led New Zealand’s economy into recession.

In 2011, the effects of the “the girl” may overshadow all of those before it.

The president of the Australian Meteorological and Oceanographic Society, Neville Nicholls, said this week: “The Queensland floods are caused by what is one of the strongest – if not the strongest – La Nina events since our records began in the late 19th century”.

The most reliable of those La Nina records is the Southern Oscillation Index (SOI), which measures the atmospheric pressure difference between Darwin and Tahiti.

The index was inspired by “gentleman scientist” and the director-general of British observatories in India, Gilbert Walker.

Walker aimed to predict India’s monsoons after a failure in 1899 caused widespread famine. He also had a personal interest – it is believed he traded in tea futures, the success of which was closely tied to rainfall in India.

His observation that the pressures at Tahiti and Darwin see-sawed, weakening and strengthening simultaneously, was the basis for the SOI.

One hundred and 10 years later, in December, meteorologists using the Walker-inspired index were astonished at what they saw.

A reading of 2.8 was the highest ever for that month since records began in the 1850s. The further away from zero the reading, the more abnormal it is. Anything above two, positive or negative, is considered extreme.

The reading foreshadowed events which were to strike Australia the hardest. La Nina and monsoon rains have combined to devastate northern and eastern Australia, claiming at least 16 lives.

New Zealand has been spared from the downpours by its location in the Pacific.

Describing the effect of La Nina, climate scientist James Renwick says: “It is like dropping a rock in a pool – you get waves radiating out. The tropical part of the Pacific is where the rock – La Nina – is dropped. And New Zealand feels the ripple that pans out from that.”

This means La Nina’s effects are not as acute by the time they cross the Tasman Sea.

The greatest threat La Nina poses to New Zealand are the tropical cyclones which breed in its warmer water.

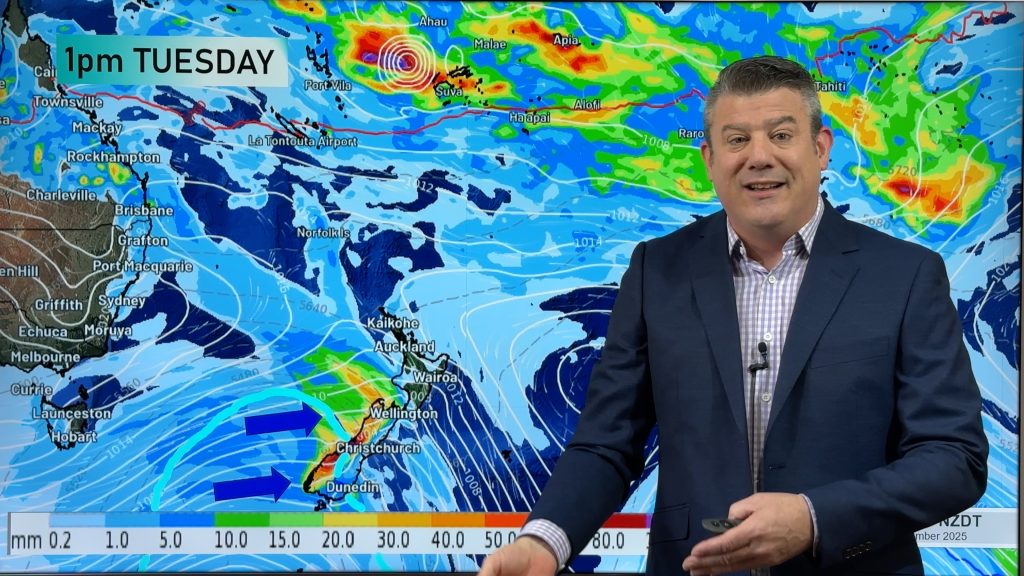

Trade winds that accompany La Nina push tropical cyclones westward. At time of writing, three cyclones were sitting north of New Zealand.

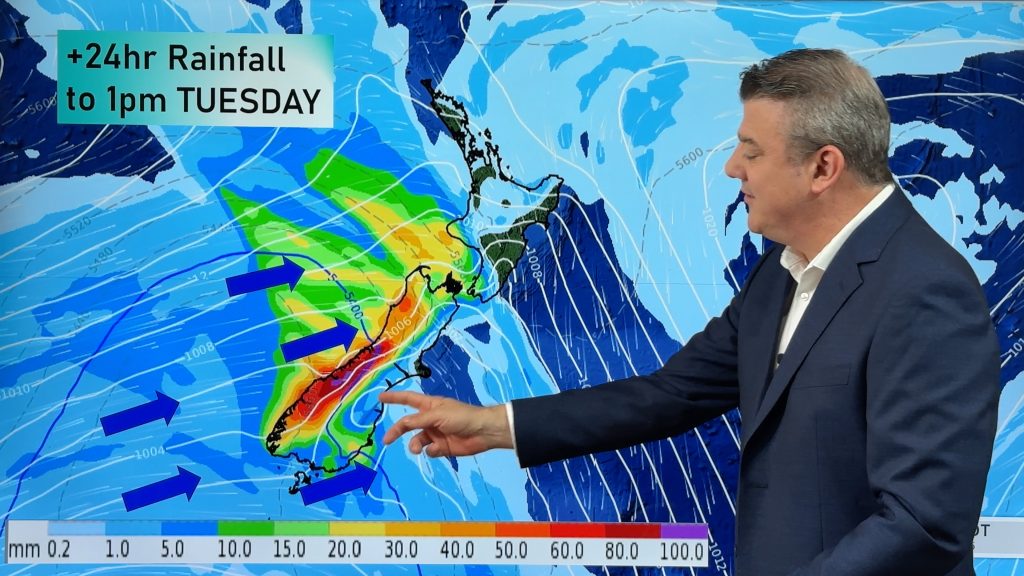

So far this summer, New Zealand’s experience of La Nina has been heavy rainfall in December and above average temperatures. But La Nina is now at her peak.

Weather scientist Dr Jim Salinger says our real taste of the cycle could arrive this week.

Tropical Cyclone Vania is currently Category Three, and has flooded Fiji and battered Vanuatu.

“We shouldn’t hold our breath. It looks like early next week the tropical cyclone should track near New Zealand, which will be our first significant event,” Dr Salinger says.

A common path for a tropical cyclone is to pass close to the North Island’s east coast.

“It may not happen,” says Dr Salinger. “But this is La Nina for New Zealand. More rain, more warmth, and, of course, tropical cyclones.”

By Isaac Davison | Email Isaac

Comments

Before you add a new comment, take note this story was published on 15 Jan 2011.

Add new comment