> From the WeatherWatch archives

An often unforgiving wind in the mainland is the Canterbury Nor’ wester, which can at times affect the psyche of the locals in the area when it blows for days on end.

David Relph has written an article based on his experiences of the fohn wind, from his early days up until now.

I had spent my childhood growing up on a sheep run at the mouth of the Rakaia Gorge, and was paying a nostalgic return visit to the area 60 years later. Within the protective bubble of our modern car, we could hear the engine labouring and feel the buffeting of the wind outside as we toiled our way up the road to the Lake Coleridge power station in the face of an old-man nor’wester roaring down the gorge. The sky up ahead, above the headwaters of the Rakaia and Mathias Rivers, looked bleak, with clouds spilling heavily over the mountains and beginning to obliterate them in a screen of grey mist. In the wide riverbed below, columns of dust were swirling across the shingle, and the trees in the shelter belts were tossing violently and leaning heavily in the wind.

My mind kept re-running childhood memories of our old Ford truck rocking violently as it ground its way in second gear up this same road to Lake Coleridge village. I was forcibly reminded that as a child I had been told that the Rakaia Gorge was the windiest place in New Zealand, possibly in the world. Now the scepticism that had come with adulthood was being dented. Perhaps those childhood recollections hadn’t been exaggerated by the passage of time after all.

Without a doubt the seemingly ever-present nor’wester is one of the more abiding memories of the weather during my childhood. The constant singing of the telephone wires; hillsides alive with the endless movement of tussocks rippling in the wind; the relentless sighing of the pines that surrounded the homestead; the excitement of awaking to see the lawn littered with small branches snapped from the trees during the night. Powerful memories, and not without foundation.

How appropriate is the name Windwhistle, given to the tiny settlement where the wind sweeps from the gorge onto the Canterbury Plains. The place is still no more than a crossroads with a small shop (once McHugh’s blacksmith’s) and the little school where I began my education. Back then the school consisted of a single corrugated-iron-clad classroom in a rarely mown paddock, sheltered by a growing pine plantation. Now it has two classrooms and a neatly mown playing field much more snugly protected by mature plantings.

Doubtless there are many places in New Zealand where the locals would dispute the claim that the Rakaia Gorge is the windiest place in New Zealand, but nobody could dispute the distinctiveness of the nor’wester and the powerful effect it has on both environment and people.

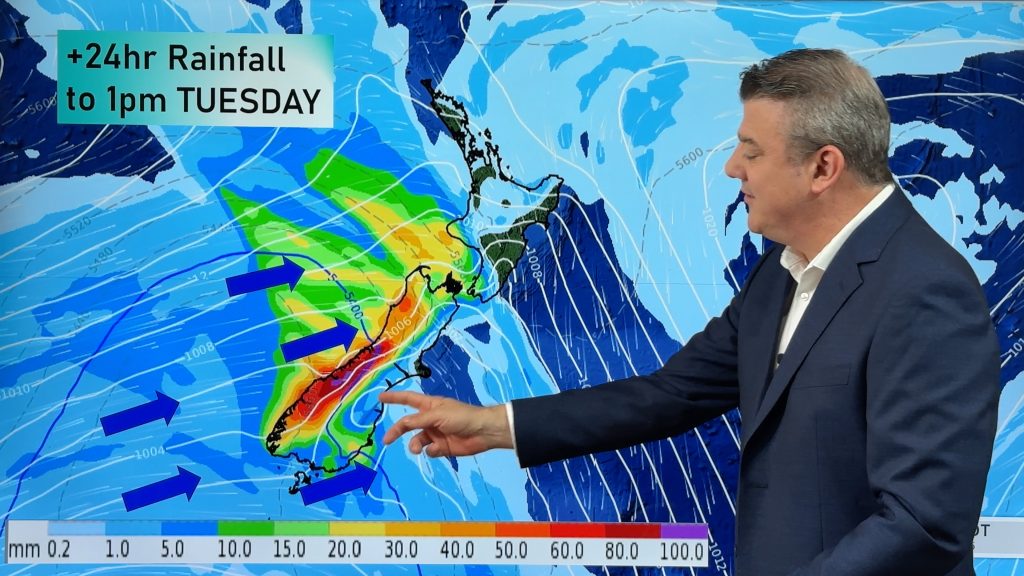

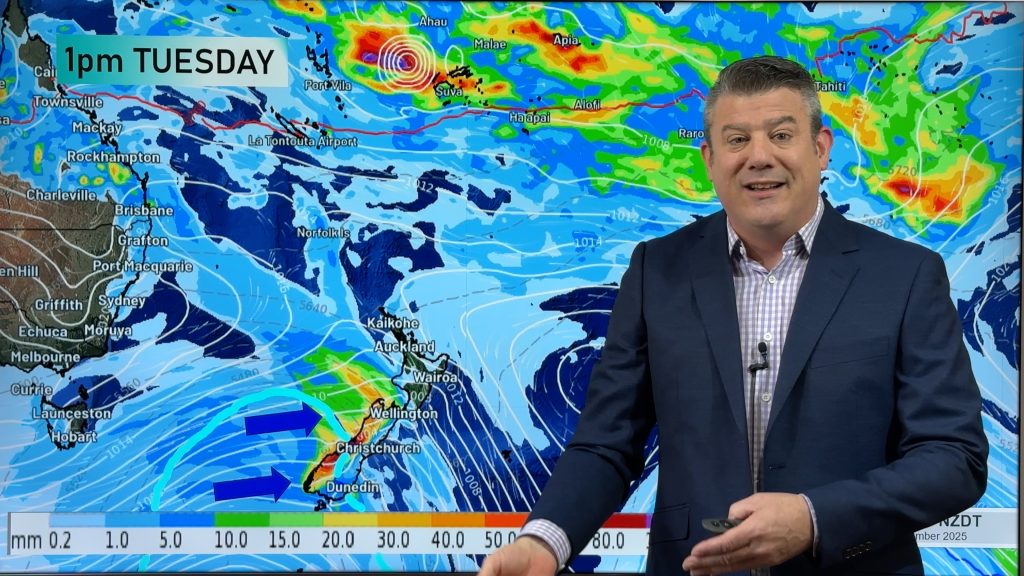

Everyone who has lived in Canterbury will be familiar with the nor’west “arch” that regularly appears over the Southern Alps, signalling the imminent arrival of a weather system from the west. Streaky clouds stretch across the mountains, leaving a gap of clear, light sky against which the ranges are clearly outlined. High-country people know that the arch is the likely precursor of strong winds roaring down the long, wide valleys of the Waimakariri, Rakaia and Rangitata Rivers, and of heavy rain in their upper reaches. Cantabrians know that it is also the signal for the arrival of the infamous nor’wester on the plains—a strong, hot, dry wind that makes conditions unpleasant all the way to the coast.

Is the Rakaia the home of the old-man nor’wester, as I have been led to believe? Wind is funnelled down each of the big rivers, but the Waimakariri and Rangitata are obstructed by front ranges before they reach the plains. In contrast, the Rakaia Gorge acts as a mighty funnel for the nor’wester immediately before it hits the flat.

A typical nor’wester sequence begins most commonly in the spring, with the gradual appearance of cloud behind the main ranges of the Southern Alps. This may build up over a period of several days. Eventually the headwaters of the rivers on the eastern side become obscured by a dense mass of grey cloud, and rain squalls move quickly down the wide valleys of the Rakaia and its large tributaries, the Mathias and Wilberforce. Heavy rain falls in the mountains and is frequently borne down the valleys by increasingly strong winds as far as Mt Algidus Station, near where the Wilberforce meets the Rakaia.

By Lake Coleridge village the rain has generally ceased, and the wind, funnelled by the steep-sided Rakaia valley, has become a gale. As it sweeps across the wide shingle flats it whips up huge dust clouds, which at times almost obscure Mt Hutt, to the south of the river.

To the north, the wind builds up in a similar fashion down the Wilberforce. The steep-sided lump of Mt Oakden, near the head of Lake Coleridge, parts this wind, the southern flow augmenting that along the Rakaia. The northern blasts directly down the lake, churning up waves as much as a metre high. It continues on over the irregular moraine hills and terraces on the northern side of the Rakaia, into the High Peak valley, over the Malvern Hills and onto the Canterbury Plains.

Comments

Before you add a new comment, take note this story was published on 24 Oct 2009.

Add new comment

RW on 25/10/2009 7:25pm

It is, I suppose, “asking for trouble” regarding nor’westers, to be living near the narrows of the Gorge, especially around the likes of Windwhistle, but in fine sunny conditions it’s a beautiful “LOTR” area near Coleridge. Down on the plains the NW wind has never bothered me in my many trips and stays in the past (mostly in Christchurch), though I much prefer it in sunny conditions to those where an arch cuts out the sun for a lengthy period. Some of the nicest days I experienced in Christchurch were some autumn or even early winter days when a light northwesterly pushed the temperatures towards the low 20s and the sun was out most of the day. Far more irksome to me than any NW-er were days when a cold easterly-quarter wind was blowing and there was plenty of cloud cover. In Wellington there is an unpleasant flavour of NW/NNW “spoiler” when ragged status moves rapidly across the sky and the sun is absent about half the time or more, and the wind is strong enough to nullify any suggestion of warmth.

Reply