> From the WeatherWatch archives

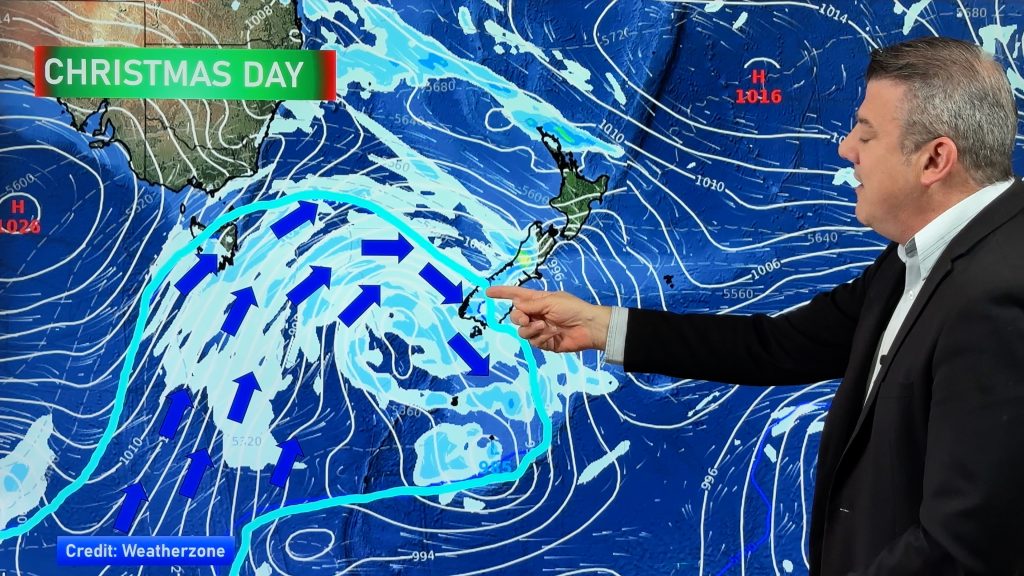

It might be those nasty looking low-pressure areas that bring the most significant weather, but it’s the big benign blobs of high pressure that play a major role in directing where that bad weather will go.

Anticyclones, because of their size and stability, act as blocks in the never-ending procession of weather systems, forcing depressions and their fronts to move around them.

Just 100km or so change in the location of the centre of the anticyclone can mean the difference between a cold showery southerly or clear, sunny weather, or the onset of warm, subtropical northerlies.

While it may seem like anticyclones make forecasting easy, in actual fact their nuances, shape and size add a degree of difficulty to predicting the weather.

There are also seasonal challenges to take into account. In summer, a big settled high tends to bring plenty of sunshine, or in other words a lack of real weather, bar some inland showers or thunderstorms if the upper atmosphere is cold enough.

But in winter, the same kind of system can bring lots of real weather which affects people’s days and can even be hazardous to business and safety if not well predicted.

Sometimes it is thick, clinging fog, sometimes glittery frost and slippery black ice, sometimes just depressing days of what is called “anticyclonic gloom”.

At the moment, the broad-scale set up across New Zealand is one of high pressure. But rarely does that anticyclone sit perfectly on top of the country. Being a long, skinny nation, there’s often bits of bad weather cuffing the far north, east or south, even if your barometer in Wellington shows an air pressure of 1035hPa.

By Guest Weather Analyst Paul Gorman

Comments

Before you add a new comment, take note this story was published on 18 May 2020.

Add new comment