> From the WeatherWatch archives

There’s talk in some weather circles that we could be in for more extreme weather from season to season resulting in more droughts and serious flooding – So how did last summer turn into a drought so quickly?

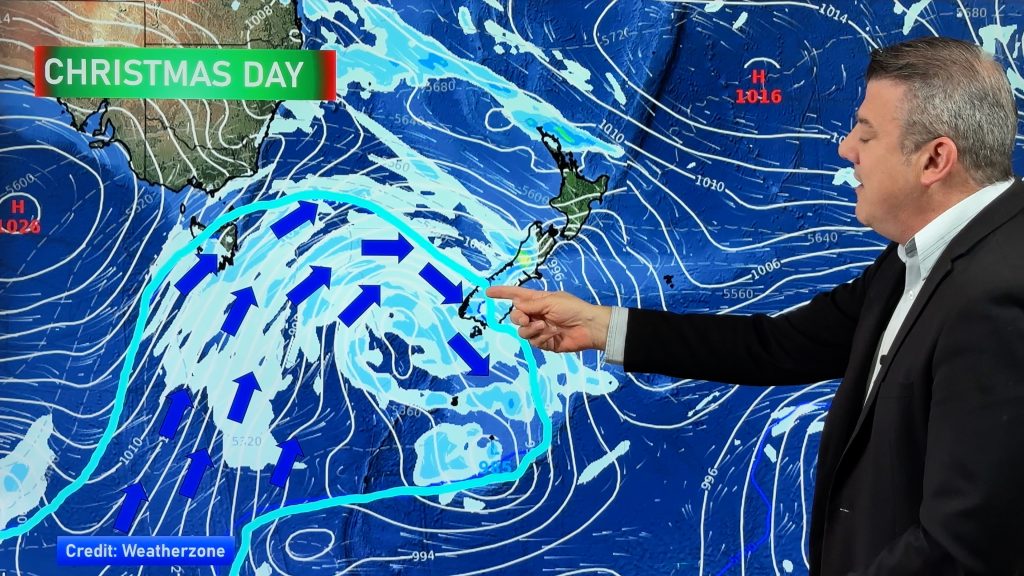

As we’ve mentioned many times before it was the anticyclones dominating our weather that stopped or slowed down any other rain-bearing systems.

It was the presence of those highs that parked themselves over the country that caused this summer’s crippling drought.

The highs fended off all possible sources of rain.

In fact, their influence was so strong that not only did they “block” horizontally across New Zealand and the Tasman Sea but they extended vertically all the way to the top of the weather-containing layer of the atmosphere, about 12,000 metres up.

Head weather analyst Philip Duncan of WeatherWatch.co.nz said well before the drought hit that there was a chance a Big Dry could impact on parts of New Zealand however one sector of the media almost labelled it as a joke.

“At the time we’d had a fairly wet spell and to call something so early on opened a few people’s eyes perhaps” Mr Duncan said.

“The signs were there early on that a prolonged dry spell could be in the offing and even though we didn’t go as far as calling a drought at the time we published several stories in regards to a Big Dry being more than a possibility”.

Victoria University school of geography, environment and earth sciences Associate Professor James Renwick said it was not yet clear how much influence climate change would have on the frequency and severity of future drought.

“We’re not sure exactly yet how it will play out. The devil is in the detail, as it often is.”

People should not expect that with climate change what had been experienced this summer would automatically be replayed again next year or suddenly become the norm.

But more extreme weather would become a way of life.

“It’s pretty clear that climate change means heavier rains when it does rain, but the flipside is longer intervals between the rains.

“The chance of what we’ve had this summer goes up, and the background level of dryness will probably go up as well – the land is warming up faster than the oceans, so moisture is tending to get sucked out faster.

“It’s easier to get to severe soil-moisture deficit conditions if you are starting from a lower base.”

The “wild card” in the climate change-drought debate was the future strength and position of the westerly wind belt, measured by the Southern Annular Mode (Sam) index, he said.

Sam had been positive in the past couple of months with westerly winds further south than average, allowing the slow-moving subtropical high pressure systems to also move south on to New Zealand. There had been a trend in the past 40 years towards that pattern and that “looked to continue into the future”, Renwick said.

However, the recovery of the ozone hole over Antarctica could act to counter that.

Warmer temperatures in the atmosphere over the Antarctic under that scenario would push back the westerlies further north.

National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research principal climate scientist Dr Brett Mullan said predicting the drought last spring would have been “exceptionally” difficult. The general outlook for summer had been for “average” conditions – with neither an El Nino or La Nina phenomenon – meaning there would be a mixture of weather. The eight global and three local computer models used as the basis for the institute’s seasonal outlooks did not . . . allow them to pick the extended dry spell.

“In October we had been looking at fairly normal conditions, but by November and December we were going for normal or below normal [rainfall] in the North Island.

“So we were seeing some signal there but when the models don’t agree, you can’t just say there is going to be a drought. I don’t know that we could have foreseen the drought any better.”

He believed it was the worst drought for many places since 1946.

“Of course it is not the worst everywhere in the country for 60-odd years, but is so particularly over the North Island. There are different factors for drought.

“In the east it’s the strong westerly winds, which are very prominent in El Nino seasons, but the other factor is the high pressure belt across the country, which has been the dominant factor with this one,” Mullan said.

it’s a complex situation calling a drought anywhere in New Zealand months in advance however if we’re heading to a future where extremes are more commonplace perhaps forecasters will have to have their wits about them even more than ever before.

Comments

Before you add a new comment, take note this story was published on 9 May 2013.

Add new comment